Emerging

Emerging

Bioengineered Bacteria to Eat Microplastics

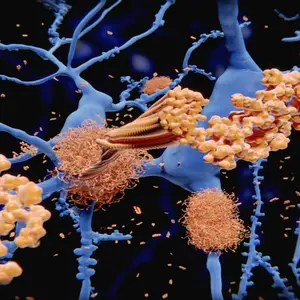

Microplastics, which are tiny pieces of plastic measuring less than five millimeters, are found almost everywhere on Earth. Each year, an estimated 10 to 40 million metric tons of microplastic enter the environment, and this amount could double by 2040 if production and waste trends continue. Unfortunately, much of these microplastics ends up in rivers and oceans, where it harms fish and marine animals and introduces toxic chemicals into the food chain. Scientists estimate that by 2050, plastic in the ocean could outweigh fish. Microplastics bioaccumulate in the human body, which is exposed to them constantly, and the deleterious health effects of this accumulation are not yet well understood.

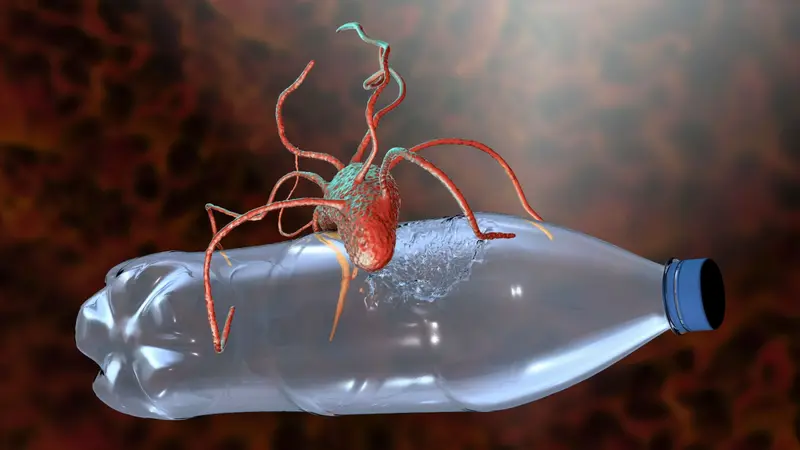

At Duke University, an interdisciplinary team of students and professors is investigating how plastics affect human health and how bacteria could be used to help clean up plastic pollution, which are made up of long chains of molecules called polymers. This process, known as bioremediation, means using living organisms (like bacteria) to remove or break down harmful substances in the environment.

Researchers are focusing on a bacterium, Pseudomonas stutzeri, which shows promise in breaking down PET, the type of plastic used in many bottles and food containers. They are testing ways to help this microbe degrade plastic more quickly by using bioengineering and a process called directed evolution to select the most effective bacterial strains.

Other team members are studying how heat might speed up the process. Since plastic becomes softer at higher temperatures, they are testing another heat-loving bacterium, Thermus thermophilus, to see if it can digest plastic more efficiently under warm conditions. The team is also collaborating with Penn State Behrend to design a solar-powered, portable bioreactor, which is a kind of controlled environment for bacteria. The scientists hope that this bioreactor could one day be used to clean up polluted areas.

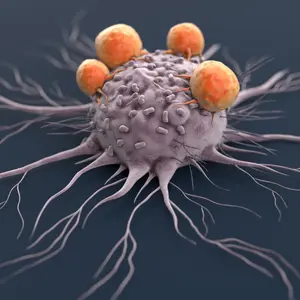

At the same time, the group is examining how the chemicals added to plastics affect human cells. Many of these additives are linked to cancer or DNA damage, and thousands more remain untested.

The ultimate goal of the project is to transform plastic waste into reusable materials, creating a sustainable circular system where plastic is continuously broken down and remade instead of ending up in landfills or oceans.

REFERENCES

Andreasen, C. (2024, April 1). Bacteria vs. Plastic. Duke Pratt School of Engineering. https://pratt.duke.edu/news/bacteria-vs-plastic/

Duke University Bass Connections. (2025). Bioremediation of Plastic Pollution to Conserve Biodiversity (2025-2026). https://bassconnections.duke.edu/project/bioremediation-plastic-pollution-conserve-biodiversity-2025-2026/ Savchuk, K. (2025, January 29). Microplastics and our health: What the science says. Stanford Medicine. https://med.stanford.edu/news/insights/2025/01/microplastics-in-body-polluted-tiny-plastic-fragments.html

By

By